Hard Yards

I spent my childhood in leafy east Auckland suburbs, or at a bach by the sea in idyllic surroundings on the Whangaparaoa Peninsula. However, there was a serpent in the garden.

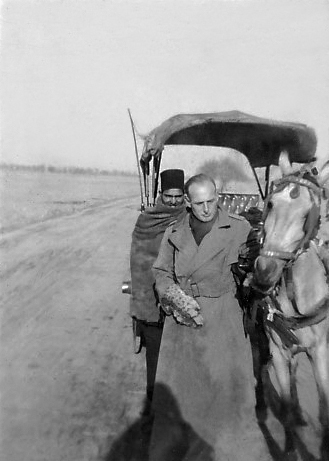

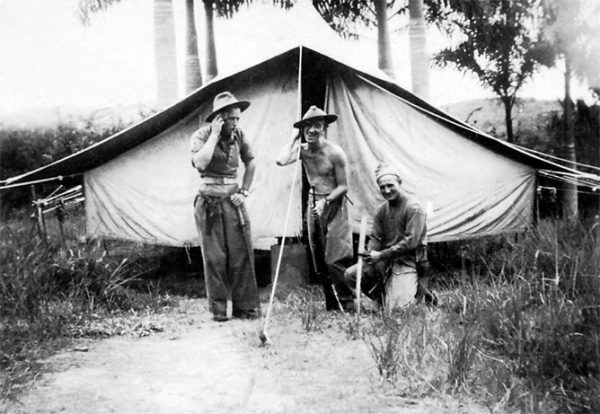

My father was unpredictable; he could be calm one minute, then erupt into rage and violence the next – definitely a “loose cannon”. This was exaggerated by mystery – I knew little about him. He was born in London in 1918, had been a front-line officer in Burma during the Second World War, and worked as a journalist in Singapore, Sydney, and Auckland after the war. His mother died when he was six, he had a brother named Fred, and he loathed his father for some reason. He was also an alcoholic – I followed in his footsteps in this regard, and also in working as a journalist. He could be fun to be around at times, but the certainty that the “truce” would not last created an atmosphere of foreboding, and probably seeded chronic anxiety in me.

My mother was a conundrum. I just never understood where she was coming from. I was informed that she never really wanted children. That might explain at least some of her behaviour toward me. She was also described as a “cold person” by a relative who knew her as well as anyone could.

The mistrust I felt toward my parents from an early age affected me profoundly. An aunt once remarked to me, with unusual candour, that she hoped I would be dim and compliant, and that she feared for my future when it became apparent that I was the opposite.

In my fifties I came across the MBTI personality typology based on the work of Carl Jung. I am an INFJ personality type – the rarest. Here’s an excellent video about what it means to be an INFJ (13 mins long, contains some tough language). I am also a Highly Sensitive Person, well and truly on the spectrum for this biological personality trait, as researched by Elaine Aron.

Domestic gothic

The claustrophobia I felt at home was intensified by social isolation. My parents had no friends. The only visitors were a few uncles and aunts, and my grandmother, the matriarch, who was treated with deference.

The key ingredients I felt that I needed for growth and development – such as understanding, approval, acknowledgment, encouragement, validation, harmony, and transparency – were either absent or severely rationed. Indeed, on many occasions my insignificance was made clear to me, reinforced by criticism, sarcasm, condemnation, violence, threats, and a phantasmagoria of controlling behaviour that my mother perfected. The main tactic employed was what has become known as gaslighting, a term with a literary origin, derived from a 1938 play – Gas Light, by Patrick Hamilton.

I spent a lot of time asking older people for permission to do relatively ordinary things, and being met with surprisingly violent responses. It took me a while to figure out that it was the asking itself that was the problem more than the nature of the request. It was better to be neither seen nor heard. One of the most disconcerting features of the situation I found myself in was its sheer randomness. I was unable to discern a pattern to my parents’ behaviour from which a strategy for avoiding further trauma could have been formulated.

A temporary respite came when I was allowed to spend school holidays staying with my Waikato cousin, with whom I got along famously. I remember the joyous feeling as the Midlands bus mounted the Bombay hills and descended into Pokeno; Auckland for a while out of sight if not quite out of mind. Pulling into Morrinsville, my destination, was like arriving in a magical kingdom.

Another enchanted sanctuary was Kawau Island in the Hauraki Gulf, where I was fortunate to spend several holidays in my mid-teens with my old friend Richard and his family. We fished, we went scuba diving, and generally messed about in boats.

I often sought to alleviate stress by acting the clown – my early forays into the theatrical realm were driven by self-preservation rather than aesthetics. But there was tension constantly in the air, similar to the mood captured by Norwegian painter Edvard Munch in his Frieze of Life series.

I dreamed that one day I would wake up from the Lovecraftian nightmare, and everything would be different – the people around me would behave rationally, and there would be explanations and rapprochements. Mostly I clung on in a state of anxiety, bewilderment, and frustration. Abusive people often have a strong vested interest in maintaining the status quo, and protecting themselves from criticism. Accountability does not exist for them.

By the time I was 17, the cracks were beginning to show. Though I didn’t know it at the time, I had become depressed. Instinctively, I swung into action. I left college, where I was a leading light of sorts, and spent as much time as I could away from home, even hiding under the house of one of my school friends. Throughout this period, I received no advice or emotional support from my family. It was as if I had ceased to exist.

One day I turned to my mother for assistance; I rang her from a public phone box. She replied, “People like you commit suicide” in a voice that was cold and mocking. I shuddered in horror, and abruptly ended the phone call. This would not be the last time a conversation with my mother proceeded in this fashion. She wrote me letters, too, many of which were – according to a counselor who was privy to their contents – “masterpieces of emotional blackmail and manipulation”. I also sought advice from my godmother – a person who had been kind to me in the past – but was angrily rejected. I knew what the consequences would be should I dare to speak with anyone outside the family, and how could I be sure that they wouldn’t betray my trust, too? This ingrained misconception kept me from reaching out for help until I was virtually at death’s door.

Obviously, I would have to find a way on my own. Out of these challenges grew a tensile emotional and mental strength that has carried me through many crises.

The fight for selfhood

It was obvious from the beginning that I am highly intelligent, sensitive, and creative. I believe that I inherited a creative talent from my grandfather. To this, I would add courage, determination, and an enthusiasm for life that has never been quenched.

I was enrolled at private schools, where I worked hard and achieved academic success. In my first years at primary school I came top in art and music. Aged six, I entered a story in an Auckland-wide competition and won. My music teacher said I had perfect pitch and should learn to play an instrument. My parents refused. By the age of nine I was composing elaborate sonnets and creating puppet shows.

My Waikato cousin and I put on horror shows for family members when we were on holiday together. These events – meticulously planned and executed – were great fun, and represent some of my most memorable creative experiences. I also participated in youth theatre for a time, something I was grateful to my parents for initiating.

There were inevitably dark clouds on the home front. I elicited several violent reactions from my father when I mentioned my intense interest in poetry. When I was 16, without asking me, my parents took my notebook from the desk in my room, and gave it to Wystan Curnow, a lecturer in English at Auckland University. Curnow duly pronounced that my creative writing efforts were devoid of talent. This finding was delightedly relayed to me by my mother.

The “Curnow incident” is one little example of the betrayal of trust that was commonplace in my home. The combination of violating a personal boundary with an attack on my love of creativity was keenly felt. It’s difficult to convey in a few lines of prose the effect of constantly being made aware that they could take whatever they wanted and do whatever they pleased, at any time, and there was nothing I could do about it. Any attempt on my part to stand my ground, forge my own identity, or even ask for reasons for things was met with antagonism. My parents noticeably enjoyed the power this gave them.

So there I was at the age of 19, already an outsider, traumatised and ill-equipped to cope with many aspects of life. I was fearful and anxious, and lacked self-belief and direction. Despite this, outwardly I fought to maintain the pleasant veneer I’d been taught to glue on as a child. I was trapped. Then I discovered alcohol, that illusory panacea.

By way of a postscript

I’ve learned some things about life as the result of my experiences. For example, it’s a losing gambit to look back in anger and become mired in self-pity, though I did plenty of that when I was drinking. There isn’t such a thing as a drunk who faces up to his problems; alcoholism is about anaesthetising self and blaming the world for one’s predicament. It’s far more difficult – and also far more rewarding, if one can stay the course – to take responsibility for existence and avoid victimhood. I have managed to achieve this goal. Several health professionals have remarked on my indomitable spirit and almost superhuman resilience and survival skills.

I am grateful to be alive, and to have achieved a modicum of self-realisation. Life tends to be fateful, beautiful, and challenging – sometimes all at once. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

> Help is available

If you need help with family violence, there are resources available in New Zealand, including: